Coal Mining in British Columbia

British Columbia exports millions of tonnes of coal every year, but plans to open more mines and greatly expand that trade have been hurt by a low coal price. Before the trade expands again in future, should British Columbians have a public debate about the coal export industry and its implications for the climate?

Coal in B.C.

By the Numbers

12 billion tonnes

Of proven coal reserves in British Columbia

26 million tonnes

Of coal produced in British Columbia annually

20

Applications for new mines in 2011

72%

Drop in price of coal since 2011

4

Mines closed in 2014-15

54.1 Million Tonnes

Of carbon dioxide released by burning annual B.C.'s coal exports.

Last Updated: May 2016

British Columbia has a long history of coal mining that goes back to the first years of settlement by Europeans. A region rich in minerals and coal, mining has always played an important role in the provincial economy. Though the province uses practically no coal today, there are large high-quality reserves that are prized for steelmaking in Asia and around the world. Since 1970 export-oriented coal mining has taken off, especially in the foothills of the Rockies in the province's northeast and southeast. Production has risen from 800,000 tons annually in the 1960s to around 26 million tons today, 40% of the Canadian total.

(Ministry of Energy and Mines)

Around 2005 the price of coal began to climb rapidly, which was soon followed by a massive increase in coal mine applications as Chinese, Korean, Japanese and American mining companies jostled to get a piece of B.C.’s relatively unexploited coal resources. The provincial government responded eagerly, investing billions in coal export terminals and railways around the province with the aim of practically tripling the province’s coal exports.

In the following years however the price of coal began a relentless decline that gained pace until, by the time of writing in early 2016, the entire coal industry stands on the precipice. All the coal mines in the Peace Region have closed, while those run by Teck in the southeast are subject to temporary shutdowns and layoffs, while simultaneously battling serious problems with selenium pollution in the surrounding waterways.

The ambitious plans for a quiet coal revolution in British Columbia seem a distant memory today, partly stymied by poor economics and partly by increasingly effective opposition by conservationists and First Nations. Yet if the price recovers it seems likely exports will expand again.

All this has happened without a public debate with British Columbians about the relative merits of the coal industry. Whereas the provincial government has launched a huge public relations campaign to promote their LNG export plans, many British Columbians remain unaware that the province has been championing a huge expansion in coal mining. If economics hadn’t intervened, the province could have conceivably been exporting 83 million tonnes of coal a year which, when burned, would have the same impact as adding two and a half British Columbias worth of emissions to the atmosphere.

It is becoming increasingly clear that the vast majority of the world’s coal must be left in the ground if civilization is to have a shot at avoiding catastrophic climate change. This raises tough questions about the wisdom of growing this industry.

- Ministry of Energy and Mines and Responsible for Housing. British Columbia Historical Coal Production and Value. Last updated May 6, 2009. http://www.empr.gov.bc.ca/MINING/MINERALSTATISTICS/MINERALSECTORS/COAL/PRODUCTIONANDVALUES/Pages/AnnualCoalProductionHistorical.aspx

Geography and History

- B.C. has billions of tonnes of coal spread around the province, but mostly in the Rockies.

- Most of it is metallurgical coal, used for making steel.

- The coal that is extracted is shipped to Asia, Europe and the USA.

- The rising price of coal until 2011 netted the industry more and more money.

A land rich in coal

Given its size, it should be no surprise that Canada contains enormous reserves of coal. Some estimates put the country’s remaining reserves at as much as 10% the global total. Perhaps 12 billion tonnes of it thought to be minable in British Columbia, concentrated in the mountainous Kootenays in the southeast, the Rocky Mountain foothills in the northeast, or on the east coast of Vancouver Island. Most of it is high quality bituminous and anthracite coal, ideal for the process of steel-making, and so is also classified as metallurgical coal. Lower grade coal best burned to make electricity is known as thermal coal.

(Vancouver Archives)

Because of these huge reserves coal mining has been an important industry in British Columbia since the beginning of European colonization; the Hudson's Bay Company began mining coal in the 1840s to power their steamers and Richard Dunsmuir became the richest man in the province by opening a series of mines on Vancouver Island. When the Royal Navy became coal-powered in the late 19th Century Vancouver Island's mines became an important strategic asset for the colonial government, cementing Victoria’s position as an important way-station in the British Empire and facilitating the young colony’s growth.

Since the early 1900s the focus of mining has transitioned east, to the Rockies, and the mines have gone from underground to open-pit, partially a result of the challenging geology of the aptly named Rocky Mountains, though there is one underground mine on Vancouver Island.

The rise of modern coal mining

Many British Columbians may be surprised to discover that the amount of coal mined in the province has risen dramatically in the past 40 years. This is partly a result of improvements in technology: huge earth-movers developed since the 1970s have replaced workers with pick-axes and exponentially improved productivity, while gigantic bulk freighters have made shipping coal around the world cheaper than ever before. Demand has also come from new places: B.C.’s high grade metallurgical coal is coveted by Japanese and Korean steel-mills, who lack their own coal resources. As a result, of the 1100 million tonnes of coal mined in all of B.C.'s history up to 2015, 85% was after 1970.

(Teck Resources)

Though British Columbia mines enormous amounts of coal, it uses practically none. While the province’s neighbours Alberta and Washington State burn coal for electricity, British Columbia does not. Indeed, through the Clean Energy Act the province practically forbade the building of any coal-fired power plants. This puts the province in the somewhat paradoxical position of effectively banning the use of coal while at the same time being the seventh largest producer of it in North America, digging up a staggering 25 million tonnes in 2015.

Those 25 million tonnes of coal were valued at $3 billion, 44% of the value of all the province’s mineral exports. That was the largest share, beating out other important mineral exports like copper and molybdenum.

In this period legislation has had some impact on reducing the environmental impact of mining in British Columbia. Most important are the land reclamation laws, first passed in the 1960s. Reclamation usually involves re-vegetating landscapes disturbed by mining, restoring natural drainage patterns as far as possible, and returning the topography to something equivalent to its original state. These are some of the strongest mine reclamation laws in the world, and every year the Technical and Research Committee on Reclamation recognizes those companies that have most successfully restored their mines. Reclamation has not been total, however. Since those laws passed, around 45,412 hectares, or 0.05%, of the province's land area has been disturbed by mining for coal and metals. Of that only 42%, or 19,422 hectares has actually been reclaimed.

(Technical and Research Committee on Reclamation)

Picking up steam

Since the year 2000 the amount of coal produced in B.C. has consistently hovered around the 25 million tonne mark. The price, however, has climbed steadily, practically doubling from 2000 to 2008, briefly dropping off during the economic collapse, before resuming its precipitous climb. By 2011 it had peaked at over $300 a tonne. This meant that the annual 26 million-ish tonnes of extracted from B.C.’s ten mines suddenly began netting greater and greater revenue, from under a billion dollars in 2000 to $5.5 billion in 2011. Mineral royalties ballooned as well, from a measly $17 million in 2000 to $316 million 2011, becoming a lucrative source of taxes for the province and growing to a quarter the value of all the province’s exports.

The Coal Industry's Deceptive Stability

In these years coal mining provided high-paying work to thousands of British Columbians. A 2011 study by Price Waterhouse Cooper for the Coal Association of Canada estimated 17,600 British Columbians were directly employed in coal mining and those jobs paid sky-high wages. The accounting firm estimated that the average weekly wage was $1,830, double the wages of people working in manufacturing and higher than any other heavy industry. A further 8,000 indirect jobs were attributed to the industry, meaning those people who work for companies supplying services to coal mines and miners. The industry has also maintained an excellent safety track record, maintaining its status as the safest heavy industry in the province.

- Ryan, Barry. Coal in British Columbia. Ministry of Energy and Mines and Responsible for Housing. 2002. http://www.empr.gov.bc.ca/Mining/Geoscience/Coal/CoalBC/Pages/default.aspx

- Ministry of Energy and Mines and Responsible for Housing. British Columbia Historical Coal Production and Value. Last updated May 6, 2009. http://www.empr.gov.bc.ca/MINING/MINERALSTATISTICS/MINERALSECTORS/COAL/PRODUCTIONANDVALUES/Pages/AnnualCoalProductionHistorical.aspx

- Ministry of Energy and Mines. British Columbia Coal Industry Overview 2015. February 2016. http://www.empr.gov.bc.ca/Mining/Geoscience/PublicationsCatalogue/InformationCirculars/Documents/IC2016-2%20coal.pdf, 1.

- Ibid., 1.

- B.C. Technical Research Committee on Reclamation. Mining in B.C. http://www.trcr.bc.ca/mining-in-bc/

- Loh, Tim. “Who’s to blame for America’s Met Coal Bust? For One, the Aussies.” Bloomberg Business. July 16, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-07-16/who-s-to-blame-for-america-s-met-coal-bust-for-one-the-aussies

- “Economic Impact Analysis of the coal mining industry in British Columbia, 2011.” Coal Association of Canada. February 15, 2013. http://www.coal.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/FINAL_Coal-Association-of-Canada_BC-EIA-Feb-15-2013-1.pdf, 4.

- Ibid., 8.

- Ibid., 10.

Boom and Bust

- The B.C. Government invested billions in coal ports and railways.

- Applications were submitted for 20 new mines.

- In 2011 the price of coal started dropping and by 2015 it lost 73% of its value.

Expanding Capacity

By 2011 mining companies around the world were responding to the rising demand for metallurgical coal—and the higher prices they could command selling it–-by going on an unprecedented splurge of mine expansion in British Columbia. Applications were submitted to open 20 new coal mines, tripling the number then in operation, in addition to major expansions to some existing mines.

(Jim Thorne)

The government saw the massive tax revenues to be won from boosting exports of $300 a tonne coal and eagerly encouraged new projects by giving companies the means to get their product to market. Namely by improving railways and expanding coal port capacity to the tune of billions of dollars. Railways connect the pitheads to the ports, and every day there are dozens of coal-laden trains snaking their way across the province towards the coast. The B.C. coal traffic is enormous, accounting for a tenth of all cross-Canada rail traffic in the country. The two railway companies, Canadian National and Canadian Pacific are outbidding each other for this lucrative business and invested $3 billion in fleet and track upgrades in 2011 alone, of which “a significant amount supports coal shipments,” according to the Coal Association of Canada.

The coal is then shipped out from one of British Columbia’s four—soon to be five—coal ports. The largest of these is the Westshore Terminal on a spit of land jutting out from Tsawwassen in metro Vancouver. Hundreds of millions of dollars have been pumped into expanding this facility and the latest $275 million tranche will boost its annual throughput to 36 million tonnes a year, making it the busiest coal export terminal in North America by a wide margin. To give you an idea of the scale, after the upgrades are complete the port will receive eight 150-wagon coal trains from the Kootenays and the United States every day.

(Wikimapia)

Neptune is another coal port in North Vancouver where the government has subsidized recent expansions from 12.5 to 15.5 million tonnes a year. In August 2014 the province gave approval to a new terminal on the Fraser River with a capacity of four million tonnes. That project is clearing the last regulatory hurdles. Another smaller terminal on Texada Island in the Salish Sea handles coal shipped by barge from Vancouver Island. In 2014 the Texada Terminal doubled its capacity to 800,000 tonnes per annum, with an eye to bigger things—plans are in the works to expand to eight million tonnes. Up north, coal from the Peace region is shipped out of the Ridley Terminal in Prince Rupert, which is itself expanding to a 25 million tonne capacity. Investments in these ports topped a billion dollars by 2013.

(City Hall Watch)

Taken together these expansions mean British Columbia will shortly have a coal export capacity of 81.3 million tonnes. This is a far cry from the usual average of 25 million tonnes. It is worth stepping back for a moment to consider the impact these new coal mines, railways and ports will have on the province. They represent a very big bet on a future dominated by coal. Many will find this surprising, as Liquefied Natural Gas has completely dominated the energy debate, and these enormous coal projects have largely flown under the radar. It is also surprising because a coal future is one that governments around the world, including the provincial and federal governments, pledged to avoid at the Paris COP21 Climate Conference.

Setting aside for the moment the moral implications of tripling exports of the most dangerous fossil fuel to our climate, if other governments around the world actually did begin taking concrete action to combat climate change, then the demand for 83 million tonnes of B.C. coal will never exist. Yet that would mean B.C. is left with a white elephant of expensive infrastructure tailor-made for the coal industry. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that our province’s very ambitious coal export plans puts us out of step with the global consensus on climate change while leaving the province vulnerable to changing global attitudes towards this resource.

The price collapse

In 2011 the price of coal began to drop—fast. Coal prices peaked at $340 a tonne coal and have since plunged precipitously to $73 tonne in the autumn of 2015. There are both demand and supply side reasons for this. Just as with LNG, Australia took the lead in the coal export race, building gargantuan new megaports that dwarf B.C.’s expansion plans for a truly astounding national coal export capacity of 350 million tonnes a year by 2009. Australia is now flooding the market with metallurgical coal, driving down prices everywhere. At the same time the Chinese economy, on which so much hope was placed for future demand, has been rapidly cooling off. Steel mills and coal mines in the industrial heartland have been shuttering their doors and in February 2016, in a shock move, the government announced the layoffs of 1.8 million workers in the steel and coal industries, as part of a fundamental and permanent economic restructuring.

(The Newcastle Herald)

Back on this side of the Pacific these shocks have stunned an industry that only a few short years ago was confidently forecasting a sunny future. As things stand in spring 2016, the British Columbia coal dream stands on the edge of ruin.

- Ibid., 5.

- “Rail, Ports & Terminals.” Coal Association of Canada. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.coal.ca/transportation/

- British Columbia Coal Industry Overview 2015. Ministry of Energy and Mines. February 2016. http://www.empr.gov.bc.ca/Mining/Geoscience/PublicationsCatalogue/InformationCirculars/Documents/IC2016-2%20coal.pdf, 11.

- “Home Page.” Westshore Terminals. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.westshore.com/#/main

- Gyarmati, Sandor. “Extensive Updates for Coal Terminal. Delta Optimist. January 17, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.delta-optimist.com/news/expensive-updates-for-coal-terminal-1.792534

- “British Columbia Coal Industry Overview 2015.” Ministry of Energy and Mines. February 2016. http://www.empr.gov.bc.ca/Mining/Geoscience/PublicationsCatalogue/InformationCirculars/Documents/IC2016-2%20coal.pdf, 11.

- “Adoption of the Paris Agreement.” United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. December 12, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2016. https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf

- Loh, Tim. “Who’s to blame for America’s Met Coal Bust? For One, the Aussies.” Bloomberg Business. July 16, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-07-16/who-s-to-blame-for-america-s-met-coal-bust-for-one-the-aussies

- Minerals Council of Australia. “Australia’s Coal Industry.” Accessed March 12, 2016. http://www.minerals.org.au/resources/coal/exports/ports_and_transport

- Yao, Kevin & Meng, Meng. “China expects to lay off 1.8 million workers in coal, steel sectors.” Reuters. February 29, 2016. Accessed March 12, 2016. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-economy-employment-idUSKCN0W205X

Coal Projects around B.C.

- Low coal prices have badly hurt the coal industry.

- All four coal mines in the Peace Region shut in 2014-2015.

- Teck Resources' five mines in the Fernie Basin are still open.

- Teck has struggled with selenium pollution problems around their mines.

Let’s zoom in to a few places around the province to gain a better understanding of the coal business and its impact on the different regions it is mined.

The Peace Region

In the northeast there were four coal mines clustered around Tumbler Ridge, three operated by American energy giant Walter Energy and one by AngloAmerican. The crunch came suddenly. Over the course of 2014 and 2015 they all shut completely and laid off thousands of workers. An employee interviewed by Business Vancouver claimed hundreds of workers at Peace Mountain Coal only discovered they were jobless when their shift manager told them at the end of the work day “Fill out your time cards. We’re paying you for today, and make sure you get on the bus to town.” Walter Energy filed for bankruptcy in July 2015.

(Vancouver Sun)

Tumbler Ridge woke up to find it was no longer a mining town, the cycle from boom to bust taking less than five years. The town is hoping to recoup some of the lost jobs as work begins on the nearby Site C Dam and the Meikle wind farm. UNESCO’s recent designation of the area as a geopark, a park of geological significance, may also help bring some tourist dollars in to town. Nevertheless the ripples from these job losses are being felt across northern B.C.: traffic at the recently expanded Ridley Coal Terminal in Prince Rupert has collapsed.

The Fernie Basin

The Fernie Basin in the southeast, Canada’s most productive coal region, has fared only slightly better. It is dominated by Vancouver-based mining behemoth Teck Resources who operate five mines close to the town of Sparwood. Teck’s community-oriented style and focus on environmental responsibility has made the company immensely popular with the people of Sparwood. Teck and coal have long been institutions in the region, and there have been trying economic times before, especially during the Great Recession in 2008 when Teck had a near death experience before being bailed out by a Chinese state owned enterprise. This time around the company managed to keep its mines open for most of 2015, barring some temporary closures to wait for someone to buy their coal. However, when the company posted a $2.1 billion loss in the autumn it triggered spending cuts of $650 million in 2016 which will include 1,000 job cuts. The thousands of people whose jobs depend on Teck are holding their collective breathes in hopes the coal price will recover.

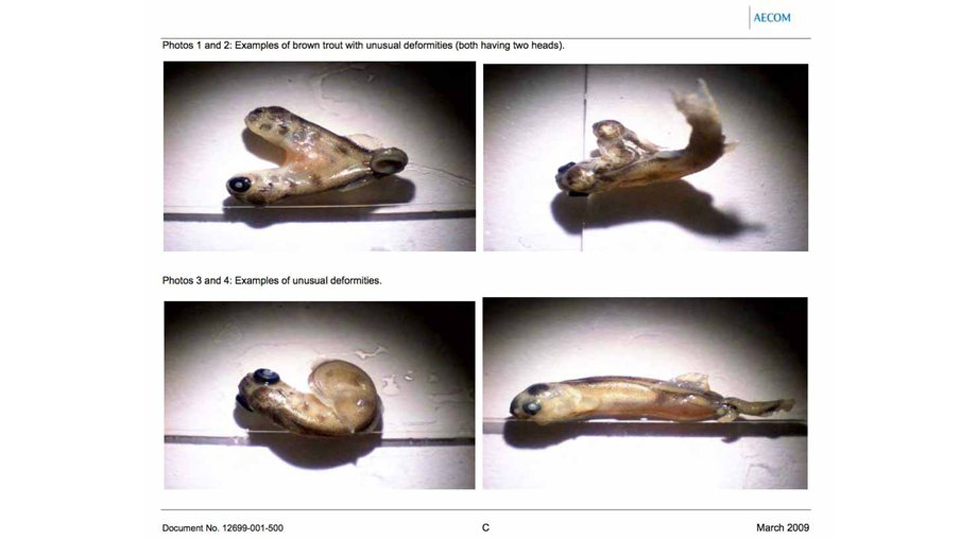

Teck’s selenium problem

These trying economic times have not helped the ongoing problems with water pollution around Teck’s mines. The Elk River flows near Teck’s coal mines and south into Montana where scientists have reported selenium levels 100 times greater than nearby rivers unaffected by mining. Selenium is a metal-like substance that leeches into water used for coal mining and can accumulate in fish eggs, causing genetic defects and potentially leading to sudden population collapses. Trout populations in the Elk River appear to be stable for now, but selenium poisoning from coal mines has become a topic of heated debate across the United States after selenium poisoning was connected to two-headed fish found by a coal mine in Idaho. This prompted the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to send a stern letter to the Canadian government in 2013, demanding action by Teck on the selenium issue, with a veiled threat they would take the issue to an international tribunal.

For their part Teck responded admirably to these concerns, making sustainability and protection of water quality a cornerstone of their business practices. Since 2011 they have been consistently named to the Global 100 Most Sustainable Corporations List and won numerous environmental awards. Teck has worked with various stakeholders in the region to develop a water quality plan and followed through on a $600 million pledge to build several water treatment plants in the area. The first of these plants came online in February 2016 and is successful in reducing selenium concentrations below 20 ppb. Unfortunately it is not clear if this will be enough, as the EPA standards say levels should not exceed 1.2 ppb, while the B.C. Ministry of Environment’s own standards are 2 ppb.

(Gizmodo)

- Wakefield, Jonny. “Tumbler Ridge adjusting to life without coal – again.” Business Vancouver. February 19, 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2016. https://www.biv.com/article/2015/2/tumbler-ridge-adjusting-life-without-coal-again/

- Loh, Tim. “Who’s to blame for America’s Met Coal Bust? For One, the Aussies.” Bloomberg Business. July 16, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-07-16/who-s-to-blame-for-america-s-met-coal-bust-for-one-the-aussies

- Wakefield, Jonny. “Tumbler Ridge adjusting to life without coal – again.” Business Vancouver. February 19, 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2016. https://www.biv.com/article/2015/2/tumbler-ridge-adjusting-life-without-coal-again/

- Jang, Brent. “Teck Resources enduring worst financial squeeze since Recession.” Business News Network. November 19, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.bnn.ca/News/2015/11/19/Teck-enduring-worst-financial-squeeze-since-the-recession.aspx

- Ibid.

- Hume, Mark. “Teck Coal facing serious water pollution in Elk Valley.” The Globe and Mail.March 21, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/british-columbia/teck-coal-facing-serious-water-pollution-in-elk-valley/article10131510/

- Simpson, Sarah. “Two Headed Trout Raises Eyebrows in Idaho.” Discovery News. February 29, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://news.discovery.com/earth/two-headed-baby-trout-from-selenium-pollution-120229.htm

- O’Neil, Peter. “Southeast B.C. coal mine draws the ire of U.S. environmental agency.” Vancouver Sun. February 6, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.vancouversun.com/technology/Southeast+coal+mines+draw+environmental+agency/7928536/story.html

- Awards and Indices.” Teck Resources. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.teck.com/responsibility/our-commitment/awards-&-indices/

- Scheitel, Leah. “Teck’s Line Creek Water Treatment Facility Operational.” The Free Press. February 17, 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-10/documents/draft-aquatic-life-ambient-water-quality-criterion-for-selenium-freshwater-2015-factsheet.pdf

- “Draft Aquatic Life Ambient Water Quality for Selenium (Freshwater) 2015.” Office of Water. United States Environmental Protection Agency. July 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-10/documents/draft-aquatic-life-ambient-water-quality-criterion-for-selenium-freshwater-2015-factsheet.pdf

- “Ambient Water Quality Guidelines for Selenium.” BC Ministry of Environment. August 22, 2001. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/wat/wq/BCguidelines/selenium/selenium.html

Environmental Opposition

- Environmentalists and First Nations have blocked many new mines.

- Mines in the Flathead Valley, at Mount Klappan and on Vancouver Island halted.

The deteriorating economics of the coal mining has meant that the surge of interest in opening 20 new mines has dried up. Yet just as big an influence was the effective opposition to these new projects mounted by environmental groups and First Nations who have won a string of victories blocking high profile projects across the province.

The Flathead Valley

For much of the early 2000s Cline Energy, a Canadian company, was pushing for two new coal mines in the Flathead Valley, just to the east of Teck’s Elk Valley projects. The Flathead Valley is a pristine wilderness, just adjacent to the UNESCO World Heritage designated Glacier-Waterton International Park. The Nature Conservancy of Canada describes the Flathead Valley as the “Serengeti of the North”, an important biodiversity hotspot with dense populations of forest caribou, bighorn sheep, elk, moose and grizzlies. In 2010 Environmental groups pressured the government into blocking the new mines by buying out Cline’s land claims. This the government did on the condition the environmental groups chip in for the bill. They succeeded in raising the money in 2012, blocking any future mining projects in the Flathead Valley.

Mount Klappan

(Tahltan Nation)

Up in the province’s northwest Fortune Minerals, a Chinese mining consortium, had been in the advanced stages of exploration on a series of mines around Mount Klappan called the Arctos Anthracite Project, one of the largest undeveloped deposits of metallurgical coal in the world. Indeed, this area has barely been touched by any development at all and because of the challenging geology of the region the mining would necessarily bear much closer resemblance to the environmentally devastating mountain-top removal mining practiced in the Appalachians than to the open-pit variety carried out by Teck.

The claim is situated on the so-called Sacred Headwaters, the watershed of the Stikine, Skeena and Nass Rivers that all feed into the Great Bear Rainforest, the largest remaining intact temperate rainforest on earth. Given the recent revelations of selenium pollution from Teck’s projects on the Elk River, and the paramount importance of robust salmon populations to the Great Bear Rainforest’s health, this project became a lightning rod of environmental activism.

In 2015 matters reached a head when the Tahltan First Nation, on whose land the mine was to be built, occupied the exploration camp and prevented the company’s employees from going to work. To defuse the situation Fortune Minerals withdrew their application and accepted the government’s offer of a buy-out until a consensus on the project’s future could be reached with the Tahltan, while retaining exclusive rights to the lucrative anthracite deposits for ten years.

Raven Coal

(Coal Watch)

A third project to get slowed by environmental groups and ultimately abandoned was the Raven project, an underground mine to be built on Vancouver Island near Courtney. Compliance Energy proposed mining 1.1 million tonnes of coal a year and trucking it out to Port Alberni, along a winding, mountainous two lane highway, down the main street of the town to waiting ships at a new terminal. When averaged out this would equal one truck every ten minutes over the course of the mine’s operating life of 16 years. The mine would employ 300 directly and several hundred more indirectly.

Immediately after the application was submitted it came under intense public scrutiny. The mayor of Port Alberni opposed the project because of the disruption this relentless truck traffic would cause to daily life in his town. Residents of the town of Courtney opposed the mine because of its close proximity—the mine is visible from the city—and the threat billowing coal dust could pose to human health. Just downhill from the mine is Buckley Bay, home to a thriving oyster industry that employs over 500 people. Shellfish are famously sensitive to minor changes in water quality, and people there strenuously opposed any development that could imperil water quality, especially after a lake beside the nearby Quinsam coal mine was found to have arsenic levels 30 times normal.

The Environmental Assessment Office rejected Compliance Energy’s application in 2013, a relatively rare move, citing a number of informational deficiencies including missing information on long term damage mitigation, inadequate plans to protect a drinking water, and insufficient consultations with First Nations. Compliance was asked to reapply after addressing these problems. This they briefly did in early 2015, before suddenly withdrawing the application because of “the built-in biases of the review process”. It appears unlikely the project will be revived.

These three examples prove that grassroots opposition to coal projects can be effective and can force mining companies to address the concerns of stakeholders. While the provincial government has been eager to push forward applications for an unprecedented number of coal mines, it must be said they have shown a willingness to listen to environmental groups, local communities and First Nations, and act on their concerns if mining companies fail to properly address them.

The low price of coal in early 2016 and sustained environmental opposition to some projects should not be seen as the end of the coal dream. The coal industry has been through downturns before, and it is expected that as soon as the price bounces back, so will the miners. All the closures in the northeast are believed to be temporary, while some applications, like HD Mining’s Murray River Project, are continuing to move forward. Determination to get things going again is hinted at in Minister of Energy and Mines Bill Bennet’s Christmas 2014 press imploring British Columbians to “Stuff [their] stockings with B.C. coal,” because “no matter the product or where it was made, it probably wouldn’t exist without B.C. coal.”

(The Globe and Mail)

- Keating, Bob. “Environmentalists’ buyout of Flathead Valley mining complete.” CBC News. September 15, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/environmentalists-buyout-of-flathead-valley-mining-complete-1.1296643columbia/environmentalists-buyout-of-flathead-valley-mining-complete-1.1296643

- “A Fortune at What Cost?” Pembina Institute. March 2008. Retrieved March 12, 2016. https://www.pembina.org/reports/Klappan-fs.pdf

- Bennett, Nelson. “B.C. pulls end-run on Anthracite coal project (updated).” Business Vancouver.May 4, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2016. https://www.biv.com/article/2015/5/bc-pulls-end-run-anthracite-coal-project/

- Kimmett, Colleen. “Could the Raven Mine Swing Comox Valley?” The Tyee. May 10, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://thetyee.ca/News/2013/05/10/Comox-Raven-Mine/

- “Mike Ruttan, mayor of Port Alberni, B.C., worried about Raven Coal Mine.” CBC News. February 9, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/mike-ruttan-mayor-of-port-alberni-b-c-worried-about-raven-coal-mine-1.2946608

- Smyth, Pamela.”Hundreds Protest Coal Mine.” Oceanside Star. January 26, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.coalwatch.ca/hundreds-protest-coal-mine

- Broten, Delores. “Quinsam coalmine shows high arsenic.” Watershed Sentinel. July 4, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.watershedsentinel.ca/content/quinsam-coalmine-shows-high-arsenic

- “Raven coal mine: Compliance Energy withdraws application.” CBC News. March 3, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/raven-coal-mine-compliance-energy-withdraws-application-1.2980134

- “9.2.1. Coal” Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.ipcc.ch/ipccreports/tar/vol4/index.php?idp=196

-

“Stuff your stockings with B.C. Coal.” Press Release. Ministry of Mines and Energy. December 13, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2016. https://news.gov.bc.ca/stories/stuff-your-stockings-with-bc-coal

Climate Change

- Coal is the most dangerous fossil fuel for the climate.

- B.C. coal exports creates enormous greenhouse gases.

- These emissions not counted under Carbon Tax or provincial climate plan.

Throughout this examination of the economics and environmental impacts of mining coal, there is a ghost at the feast that has gone largely unmentioned: climate change. As we discuss in our coal article, burning coal produces more greenhouse gases than oil or natural gas, both in the amount released per unit of energy and in total contributions to climate change. The IPCC is unequivocal: coal is so damaging to our climate that the urgency of phasing it out is greater than oil or natural gas. It is looking increasingly likely that human civilization’s odds of avoiding catastrophic climate change will hinge on how soon we can stop using coal and how much of it we can leave in the ground and avoid burning at all.

(Shanghai Daily)

Which emissions we choose to count

The B.C. government agrees in principle with this point and is aware that greenhouse gases will have an impact on the climate no matter where on earth they are burned. Yet the only emissions included in the Ministry of Environment’s statistics are those released during the mining, processing and transporting of the coal to port. Under that metric coal accounted for about 3.1 million tonnes of Co2/eq. in 2007, about 5% of the province’s total according to a study by the Pembina Institute.

But what if we were to include the emissions released when the coal was burned in steel mills on the other side of the world? Burning a tonne of coal creates roughly 2.04 tonnes of carbon dioxide. Doing the math, then we find the coal export industry would account for a tremendous 54.1 million tonnes of Co2/eq. a year, equal to 81% of all the province’s 2007 carbon emissions. This also happens to be the same amount of GHG released by all the mining, upgrading and refining done in the Alberta oil sands (though not including the burning of the oil). As a study by the Dogwood Initiative noted, this is the equivalent of building 16 coal fired power plants in the province or adding 11.7 million new cars to B.C.’s roads, four times the number of cars in the province.

Had the bottom not fallen out of the coal market over the last several years then the coal industry today would be much larger and the problem drastically worse. If all of the new port facilities were to operate at their planned capacities of 81.3 million tonnes of coal a year, then British Columbia would be exporting 168 million tonnes of GHG, or the equivalent of 2.5 British Columbias. When speaking in these scales all the other efforts at reducing emissions being taken by thousands of British Columbians, like taking transit or turning down the heat, begin to seem absurd.

BAR GRAPH FOR EMISSIONS COMPARISON

How can one explain this paradox of a province that sets ambitious GHG emissions reduction targets at home while simultaneously exporting millions of tonnes of the dirtiest fuel? There are two identifiable legislative causes. The first is that the Environmental Assessment Office has no mandate to consider GHG emissions at any point when evaluating a project. As Erin Gray, a UVic graduate student, explained in a study presented to Premier Christy Clark in 2015, this is a glaring oversight and environmental assessment offices in other places do a better job of taking climate change into account. California, Washington and Oregon, for instance, all consider lifecycle GHG emissions in their environmental assessments. This is one of the reasons why several new coal terminals in Washington that would export coal from Wyoming to Asia are struggling to gain approval. Instead those American coal shipments are being routed through Robert’s Bank in Metro Vancouver. This is perhaps an indication of how difficult it would be to justify actually building any coal infrastructure in B.C. if the climate impact was measured when deciding whether or not to approva a project.

(Climate Crocks)

Secondly, the provincial carbon tax excludes the emissions that result when B.C. coal is ultimately burned in Asian steel mills. If these emissions were to fall under the carbon tax, which was set to $30 a tonne in 2012; it would cost the coal companies $1.62 billion instead of $93 million. It seems likely that adoption of both these policies would bring the B.C. coal industry grinding to a halt.

Should we let coal fail?

Would it be a bad thing if we imposed these regulations on the coal industry? Both from an economic and moral standpoint, there are strong arguments that the answer is no, at least in the long term. Economists are increasingly sounding the alarm of the threat of a so-called “carbon bubble” in investment markets. As Mark Carney, former Governor of the Bank of Canada explained in a 2014 speech to Lloyd’s of London:

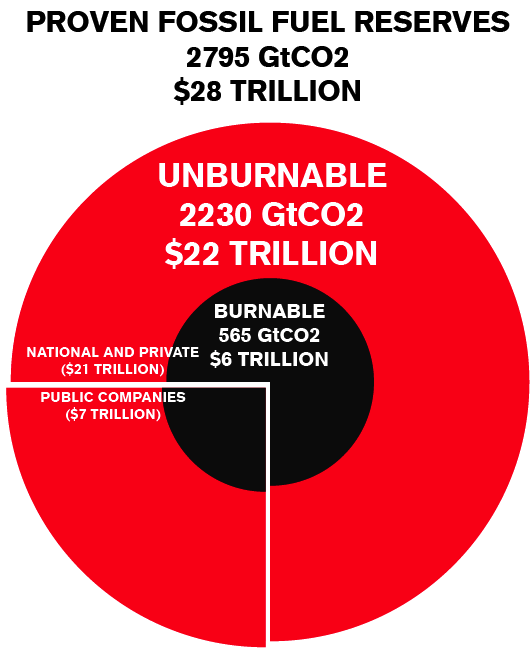

Take, for example, the IPCC’s estimate of a carbon budget that would likely limit global temperature rises to 2 degrees above pre-industrial levels. That budget amounts to between 1/5th and 1/3rd of the world’s proven reserves of oil, gas and coal. If that estimate is even approximately correct it would render the vast majority of reserves “stranded” – oil, gas and coal that will be literally unburnable without expensive carbon capture technology.

This means, he went on to say, companies that are invested heavily in fossil fuels are becoming increasingly vulnerable to sudden and major write-downs of the value of their assets. As governments around the world, inch closer to strong action on climate change, they may pass laws enforcing a carbon budget, or any of a range of other legislative options that could cause markets for fossil fuels to dry up, or render huge parts of the world’s fossil fuel reserves and infrastructure worthless.

When squaring the circle of climate science and economic policy, it becomes evident that coal has no long term future unless we are to resign ourselves to a worst case climate scenario. At the very least it makes the threat of overbuilding coal infrastructure more likely to result in economic exposure in the future, something the coal industry is discovering from the depressed coal price right now. In one sense it is fortunate the price collapsed as soon as it did. If it happened after loans were taken out, ground broken and workers hired for many of the 18 new mines that were on the on the drawing board then British Columbians would be feeling a lot more economic pain today.

Christiana Figueres, executive secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, laid out the risk of a carbon bubble to corporations and governments in stark language.

If corporations continue to invest in new fossil fuel exploration, new fossil fuel exploitation they are really in breach of their fiduciary duty because the science is abundantly clear.

Understanding the science, the fact is that we have to move to low-carbon no matter what, with or without policy. We will move to a low-carbon world because nature will force us, or because policy will guide us. If we wait until nature forces us, the cost will be astronomical.

So it is actually in everybody’s interest to get the policy that will allow us to move in a structured way that does not call upon a systemic risk of falling off a cliff all of a sudden and then that capital needs to be shifted overnight. So what you want is an organised structural process that allows you to move forward and shift the capital in a safe and predictable way. If we don’t do that we will go to low carbon anyway, but it’s going to be much more expensive and it’s going to be very unpredictable where we are going to come up.

The idea of deliberately strangling the coal industry will no doubt cause economic pain and provoke heated opposition. Yet not that many people actually work in coal. Those 17,000 jobs the industry provides account for some 0.7% of British Columbia's total. About as many people worker in clean energy. It is also worth noting that if we were to include the burning of these coal exports in our emissions measurements, this rather small industry has an enormous impact on B.C.'s global climate change impact. It will likely be possible to manage the move away from coal mining. In the past fishing and forestry employed orders of magnitude more people than they do today, but the economy was able to survive as those industries declined hugely in relative importance.

(Mining and Exploration)

It is becoming increasingly apparent that the moral imperative of our time, and perhaps all history, to leave as much coal—and oil and natural gas—in the ground as possible. It would be easy to argue that British Columbia’s tiny impact on global climate is small enough that we can carry on as if it doesn’t matter, but we must remember this exact same debate is being held in every national, provincial or state capital on earth, and if all follow that course then the future begins to look very grim indeed. Yet even worse, this line of thinking obscures the true magnitude of the coal expansion plans that have been proceeding quietly while LNG claims the spotlight. B.C. coal is not a small contribution to Canada’s emissions, and it threatens to become a much bigger one. The stakes are high enough that we must take the risk of some short term economic pain to show solidarity with those in the world who cherish a future.

- “B.C.’s Dirty Secret: Big Coal & the Export of Global-Warming Pollution.” Dogwood Initiative. Retrieved March 12, 2016. https://dogwoodinitiative.org/publications/reports/coalreport, 34.

- Ibid., 35.

- “Greenhouse Gases.” Alberta Government. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://oilsands.alberta.ca/ghg.html

- “B.C.’s Dirty Secret: Big Coal & the Export of Global-Warming Pollution.” Dogwood Initiative. Retrieved March 12, 2016. https://dogwoodinitiative.org/publications/reports/coalreport, 9.

- Gray, Erin. “Blind Spot: The Failure to consider climate in British Columbia’s Environmental Assessments.” UVic. Environmental Law Centre. September 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.elc.uvic.ca/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/BlindSpot-Climate-in-BC-EA_Sept2015.pdf

- Santos, Melissa. “Coal export terminals: A source of jobs, or coal dust and climate change?” The News Tribune. November 20, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.thenewstribune.com/news/politics-government/article45509235.html

- “B.C.’s Dirty Secret: Big Coal & the Export of Global-Warming Pollution.” Dogwood Initiative. Retrieved March 12, 2016. https://dogwoodinitiative.org/publications/reports/coalreport, 42.

- “Breaking the tragedy of the horizon – climate change and financial stability – speech by Mark Carney.” Bank of England. 29 September 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/speeches/2015/844.aspx

- Mathiesen, Karl. “Will Fossil Fuels melt the global economy?” The Guardian. March 6, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2016. http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/mar/06/could-fossil-fuels-melt-the-global-economy-carbon-bubble