Douglas Cruickshank

How do you design a “Keep Out!” sign to last 10,000 years?

The Department of Energy is creating a vast monument to scare future trespassers away from radioactive waste sites. Their plan: A granite Stonehenge thing with warnings in Navajo!

Imagine you’re part of an archaeological expedition 6,000 years from today, stomping around the desert in an area known long ago as Yucca Mountain, Nev. You are looking for the remnants of a once flourishing civilization, a nation state that apparently called itself the USA back in 2002. You’re 10 days into your quest, not finding much of anything, when one of your team runs up, all sweaty-faced and panting, insisting that you come see what he’s discovered.

You follow your flushed, jabbering colleague around a rocky outcropping, and there, vividly etched on a granite monolith, is a towering reproduction of Macauley Culkin in “Home Alone,” hands to face, mouth agape; or maybe it’s one of Francis Bacon’s shrieking pope paintings or Edvard Munch’s “The Scream.”

You don’t recognize any of these startling cultural icons from the distant past; you don’t know who made them, or what they symbolize. Hell, you don’t even know that they’re cultural icons, but the whole scene briefly scares the bejesus out of you. Then, like Howard Carter stumbling on the tomb of Tutankhamen, you experience a serious rush of exhilaration, aggravated by a serious case of the heebie-jeebies, as you realize that you’ve just chanced on a history-making breakthrough, a discovery of earthshaking significance.

So, which do you do? 1) Immediately pack up the entire expedition and evacuate the area never to return? 2) Waste no time in commencing a major archaeological dig and cementing your place in history?

Amazingly enough, the folks over at the U.S. Department of Energy are banking on curious humans (or whomever) from future millennia to go for Door No. 1.

As it becomes increasingly likely that, despite Nevada’s protests, President Bush will get his wish for Yucca Mountain to become the nation’s central nuclear waste repository (the House has approved it by a 3-1 margin; the Senate may vote on it as early as next week), the doings of the DOE, which will be charged with building the facility, warrant greater attention.

For the last two decades, it has been the daunting, if not nutty, business of the department to study and design warning monuments for radioactive waste sites, such as Yucca Mountain or the already functioning Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in Carlsbad, N.M. When I heard about this eerie undertaking, I called the DOE’s Office of Civilian Radioactive Waste Management’s Yucca Mountain Project (YMP) to see what I could learn about the harebrained — I mean, farsighted — scheme.

The YMP has a toll-free line staffed by real people, specifically established to field questions from yo-yos like you and me. When I called, a very nice, patient, soft-spoken woman named Jenny McNeil picked up the phone.

“You know,” McNeil told me, “there has been a lot of research, since the ’80s, in an effort to come up with plans for monuments that would transcend specific cultures and languages.”

Ms. McNeil was a kind soul, and her voice had a definite calming effect, but she wasn’t a fount of information, so I called Sandia National Laboratories where, in 1991, the monument plan was first described in a study produced by the lab for the DOE. I talked to an official there (who asked not to be quoted by name). “Is this something that’s actually going to happen,” I asked him, “or is it a dead subject?”

“Oh, no, no, no,” the Sandia official told me. “It definitely will happen.”

The monuments are intended to last for thousands of years — the waste may stay toxic for as long as 100,000 years. If everything goes as the DOE hopes, an archaeological expedition tens of centuries hence will take one look at these structures and hightail it in the other direction — just like we do now whenever we come across mysterious ancient monuments covered with strange inscriptions and odd images.

What are they thinking?

And they are big thinkers over at the DOE. They’re not talking about slapping up a few signs with a red circle and diagonal line over a mushroom cloud or a glowing mutant, or even something slightly more ambitious like that unnerving black obelisk in “2001: A Space Odyssey.” No, what the DOE has in mind is more on the order of Stonehenge, but with a better class of stone — granite — and magnets.

Magnets? Of course. You need magnets to “give the structure a distinctive magnetic signature.” (I knew that.) But also because they nicely complement the “metal trihedrals” (three-sided pyramids) that will provide that all important “radar-reflective signature.” Very Captain Kirk, and more and more fascinating as you get further into its psychotic science fiction novel aspects.

Anyway, according to a report in the May/June issue of Archaeology magazine, in a reverse archaeology exercise, the DOE brought together “engineers, archaeologists, anthropologists, and linguists to design effective warning structures capable of lasting 10,000 years … Using archeological sites as ‘historical analogues.’” A summary analysis of the DOE report on the Environmental Protection Agency Web site explains that “The conceptual design for the PIC (‘Passive Institutional Controls’) markers” includes a berm surrounding the area, 48 granite monoliths, “thousands of small buried markers, randomly spaced and distributed,” an information center located aboveground, and “two buried storage rooms.”

You’ll note there’s no provision for a gift shop or children’s play area, but I suspect those design oversights can be easily corrected at the same time they put in the handicapped ramps.

So, you might ask, “What’s this thing going to run us?” Calm down, taxpayers, it’ll be a pittance. The materials will be cheap, says the EPA, pointing out that “materials of high economic value are less desirable because they may encourage removal and/or destruction of markers.” Good point — that’s where the Egyptians slipped up. No gold facings for us.

Figure the whole job’s going to cost a mere $150 to $200 million. Chickenfeed for those of us who don’t fancy our future relatives looking like phosphorescent iguanas.

To get a closer view of one of these proposed hot zone follies, come, let’s take a walk through, and for god’s sake, don’t touch anything.

According to the EPA document, the “inner core” of the 33-foot-tall berm “will consist of salt.” OK, sure. Salt. Most people turn and run at the sight of salt. This berm surrounding the “repository footprint” (I love wonk-speak) is the first line of defense. The thought, I guess, is that if our year 8002 archaeologists first begin to dig into the berm, they’ll strike the mound of salt. “Salt!” someone will bellow. “Let’s get the hell out of here!” And the expedition leader will try to control the ensuing frenzy. “Better clear out,” he’ll say. “I don’t like the looks of this. Fill the shakers then let’s beat it!”

But if curiousity gets the better of our explorers, and they just walk right over the berm and head for the monuments, they’ll first come across 16 structures that will “consist of two granite monoliths joined by a [5 foot] long tendon, with a buried truncated base, [22 feet] high, including the tendon, and a [25 foot] high right prism that will be [4 feet] square. The upper stone will weigh approximately [40 tons], and the base stone will weigh approximately [65 tons].” And that’s just the first bunch.

Farther in, at the “perimeter of the controlled area,” are 32 more granite monoliths. Altogether, these 48 100-ton puppies alone will cost about $30 million according to the EPA estimate. But given how government contracts go, we can safely triple that and still be under the actual cost. Shipping extra. Seems like a lot until you consider that the price includes engraving.

No, there’ll be no monograms, no floral patterns, but each monument will be inscribed with “messages in seven languages: the six official United Nations languages (English, French, Spanish, Chinese, Russian, and Arabic) and Navajo.” Navajo? Great. The Hopis are going to be so pissed. With all due respect to the Navajo, a fine people we’ve done everything in our power to drive into extinction (there are about 250,000 now living in the U.S.), please raise your hand if you think our relatives 6,000 years down the pike are likely to be reading Navajo. Heck, why not Sanskrit or Eskimo?

And what are these inscriptions going to say? Will they be your basic banal warnings, the type of thing we paid so much attention to as kids, or maybe something more effective, like the first chapter of “The Bridges of Madison County”?

The DOE plans to separate the messages “into different levels of complexity,” assuming, I suppose, that even 6,000 or 8,000 years from now there will be slow readers who don’t much cotton to subtlety. Always thinking ahead, the DOE plans to road-test the inscriptions to check “the comprehensibility of messages among a cultural cross section of the U.S. population.” Sounds reasonable, but let’s take it a step further. When a Lakota Sioux gentleman doesn’t comprehend a “No Trespassing” sign written in Navajo or Arabic, what’s our next move?

Images, of course! One surface of the polished, four-sided monuments will feature “diagrams.” That’s fine. Pictures are good, and a welcome respite from all the reading, but at the risk of second-guessing the experts, may I suggest a simpler, more surefire alternate plan? A 15-foot-tall reproduction of Lucien Freud’s ghastly-but-true portrait of Queen Elizabeth, or perhaps a collection of stills from “Glitter” starring Mariah Carey, or anything from the brushes of Thomas Kinkade Painter of Light, accompanied by 500 words from Lynn Cheney’s novel, “The Body Politic,” translated into Urdu.

Trust me, there is no conceivable circumstance, now or at any time in the future, under which a sentient being confronted with such a display would not be deeply alarmed and motivated to gallop in the opposite direction. Just a suggestion, free of charge.

Now we get to the good part: the buried storage rooms and information center. To cook up these, the DOE once again turned to the ancients for inspiration. They considered Newgrange, a passage grave in Ireland thought to be more than 5,000 years old; the Great Pyramids at Giza, Egypt, 4,500 years old; rock art done by Australian Aborigines 25,000 to 35,000 years ago; and the Acropolis in Greece, which has been standing for 2,400 years.

Not to bring up an unpleasant subject or be tiresomely pedantic, but given that the stuff we intend to plant at Yucca Mountain may remain seriously nasty for, like, 100,000 years, how does the longevity of any of the above apply to this project? Well, remember that the EPA only requires that the warning monuments last 10,000 years. After that anyone who wants to go nosing around the boondocks is on their own.

Where were we? Oh yes, the buried rooms and info center, cozy granite spaces with no restroom facilities and no seating. The roofless information center will have its walls inscribed with details about “the disposal system and the dangers of the radioactive and toxic waste buried therein.” There is no provision for videos, pets are allowed — granite’s very forgiving when it comes to messes. The center will sit up high to facilitate good drainage — always a plus for rooms without roofs where incontinent pugs may forget themselves.

The two buried storage rooms are another matter. If you liked those old movies about the building of the pyramids as much as I did — humongous blocks sliding hither and thither, hysterical slaves getting sealed into secret chambers — you’re going to love these. The rooms will be constructed of huge granite slabs “joined by fitting the pieces into slots … to eliminate the need for mortar, grouts, or metal fasteners.” This is a good call. The three-year-old grout on my tub is already doing disgusting things, and don’t get me started on zippers.

My favorite part is the entrance to these rooms. It will be a plugged hole, two feet in diameter. Once our archaeologists of the future pull the plug and wriggle into the room, they’ll find “tables, figures, diagrams and maps” engraved on the walls. However, if we look at the current, up-swinging weight statistics for U.S. adults and children and figure that the trend will continue over the next several thousand years, we must assume that we’ll then be looking at a population that resembles overinflated pregnant manatees, and their likelihood of getting through a 2-foot aperture is slim to none. Of course, they did manage to get Winnie the Pooh out of that hole. Maybe we could inscribe that chapter next to the plug.

Then, buried all around the site, will be the “thousands” of small inscribed warning markers, made of “granite, clay and aluminum oxide.” The DOE experts based this idea on the Code of Hammurabi, an inscribed stone slab found in Iraq (don’t tell Dubya it was found in Saddam’s country or we’ll have a replay of the pretzel horror) and Mesopotamian clay tablets. I figure our markers will feature Jewel’s poetry on one side and select excerpts from Nancy Reagan’s “My Turn” on the other.

That’s about it. Your tax dollars at work.

Now, I’m not a scientist, so maybe this whole project makes a lot of sense to someone. A scientist, for example. And don’t get me wrong, I don’t want to be a wet blanket or soft on terrorism. Building these monument thingies sounds like a patriotic hoot. I think they’ll look very cool and be inexpensive to maintain.

I guess we just have to accept that, as with so much our government does, the whole plan’s a little kooky, but in a sweet way. Apparently none of the experts who were consulted suggested that putting up our own Stonehenge might accomplish the same thing that the original Stonehenge (or Newgrange, or the Pyramids) has — endless poking about, drilling and excavating by experts, nonexperts, tourists (and their pets) and freelance goofballs.

In fact, I’m guessing that Yucca Mountain or the Carlsbad site might be selected, a few thousand years down the road, as a perfect spot for some futuristic version of our own Harmonic Convergence celebrations of a few years back. In which case, we might want to tack on a few million for stadium seating and some bathrooms.

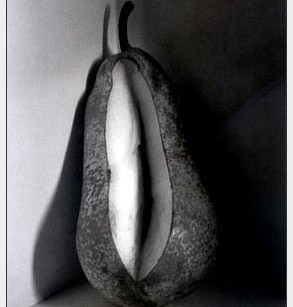

Pomegranate porn

Photographer Flor Gardu

Photographer Flor Garduño says that seven out of 10 of the models she worked with on her new book, “Inner Light,” a collection of nudes and still lifes, have gotten pregnant.

“Among my friends,” Garduño tells poet Verónica Volkow, who wrote the introduction, “word started getting around — it was a joke — that if someone wanted to get pregnant, she had to pose for one of Flor Garduño’s photographs … one of the models got pregnant, even though she was using birth control.” Still another woman saw Garduño’s lush black-and-white images and “a short time later she also got pregnant,” the photographer says.

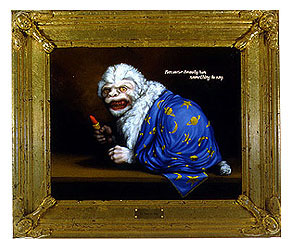

Continue Reading CloseSexy monkeys and mutant bunnies

Painter Laurie Hogin uses the style of Old Masters and a frightening menagerie of beasts to illustrate the nightmares to be found in the American dream.

When artist Laurie Hogin, 39, was a child, she lived in a suburb of New York adjacent to a 600-acre woodland. “It belonged to some old guy who just wasn’t going to sell it,” Hogin says, “so we had these woods to play in — me and my two friends. It was a wonderful, safe place for us. We were all interested in what was then called ecology; we’d see foxes, deer, wild turkey, pheasant, we’d find mushrooms. But it was a ravine with a road above it and occasionally people would dump tires, garbage and 55-gallon drums. This outraged us.”

Continue Reading Close“The Partly Cloudy Patriot” by Sarah Vowell

A "This American Life" commentator celebrates nerds and explains how to love your country without turning into a boorish, jingoistic, kitsch-crazed lout.

Wouldn’t it be nice if you could be a patriot without having to fly the flag from your porch and the antenna of your car every day, if you could skip applauding crappy, gung-ho songs about how great America is, cheering saccharine, saber-rattling speeches about how great America is, and otherwise wallowing in all the lamebrained, jingoistic posturing that now seems required behavior for U.S citizens who wish to demonstrate a commitment to their country? Yes, it would be very nice.

Good news: At least one of us has managed to pull it off. In her third book, “The Partly Cloudy Patriot,” Sarah Vowell does a bang-up job of being a good American without being a terrible bore. A solid thinker with a warm heart and a smart mouth, she loves the U.S. in much the same way that one loves one’s family (or perhaps a favorite flea-bitten old dog) — acutely aware of its many shortcomings, but true-blue to the end. “My ideal picture of citizenship,” Vowell writes, “will always be an argument, not a sing-along.”

Continue Reading Close“Normal will never happen again”

The author of two books about coping with sudden death talks about the emotional fallout of losing someone without having had a chance to say goodbye.

In October 1997, a bee stung Brook Noel’s 27-year-old brother, Caleb, a professional athlete. Neither he nor anyone else in his family was aware that he was severely allergic to bee stings. He went into anaphylactic shock and died the same day. In the days that followed, trying to grapple with the trauma of losing her brother, Noel went looking for a book that would help her cope. “There was nothing on sudden death,” she says. “It was all on terminal illness.”

So she wrote a book herself. The publication of “I Wasn’t Ready to Say Goodbye: Surviving, Coping and Healing After the Sudden Death of a Loved One,” coauthored with Pamela D. Blair, led to media attention. Later, five months prior to the 9/11 attacks, Noel was asked to join the 48-member Family Support Team of the National Air Disaster Alliance.

Continue Reading CloseThe life of the Dead

Band insider Dennis McNally talks about his new 600-page biography of the Grateful Dead, and answers questions about their long, strange trip.

Even the many who have fond recollections (or any recollections at all) of the ’60s have heard just about as much as they can bear about the 20th-century decade that can’t get over itself.

And yet, there is always more — flashbacks, confessions, photos — for those whose appetite for the past might never be satisfied.

Most recently, the era is plumbed in “A Long Strange Trip: The Inside History of the Grateful Dead,” a 600-page memoir by the band’s publicist, Dennis McNally. In truth, it’s not just about the ’60s — the book hits 1970 about midway and continues on through half of the ’90s. And McNally does not throw avid fans of the band, or the ’60s, a mere bone. His history of the quintessential psychedelic band, and the strangely intoxicating waves it made, is an entertaining, picaresque, and exhaustive contribution to pop culture anthropology.

Continue Reading ClosePage 1 of 16 in Douglas Cruickshank